|

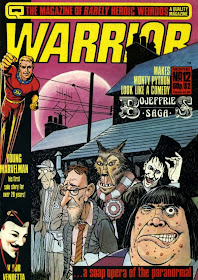

| Art by Woodrow Phoenix. |

In the following you can read an imaginary tale - The wonderful wardrobe of Alan Moore - featuring... "stylist" Alan Moore, written and illustrated by acclaimed British artist and writer WOODROW PHOENIX. In my humble opinion, the piece is - without any doubt - one of the gems contained in the tribute book.

Posted on this blog with the author's permission.

Posted on this blog with the author's permission.

The wonderful wardrobe of Alan Moore

© Woodrow Phoenix

When Alan arrived in Mainstream City, he seemed to be the same as everyone else. He blended right in with all the residents with their hats and overcoats, though you might have noticed the fancier stitching and the rather higher than average quality material of his overcoat if you paid attention to such things.

He soon found himself a place to live and a job, made friends and went to church just like everybody else, but there was something about him that made him stand out. Eventually people figured out what it was. It was the way he dressed. Even though he wore the same things as everyone else, he wore them differently. It was all in the details. Hand finishing. Linings in unusual fabrics. Bias cutting. Seams that were stitched rather than fused or glued.

According to Alan there was nothing especially noteworthy about any of this. He came from a tradition of hard work and attention to detail, he said, and that was all there was to it.

However, while he had begun by branching out, by subtly altering the details of traditional tailoring, he began feel the restrictions of this approach. He decided to go further. He went off in entirely new directions with radical styles and some rather challenging choices of colour and fabric. People noticed. People talked. He became the focus of quite a lot of attention and speculation about what he might make next.

It was remarked upon that he never seemed to wear the same piece of clothing twice. He said it was true: there were so many styles in the world, why confine yourself to the same items over and over?

Not long after that, Alan saw that his discarded clothes earmarked for recycling were vanishing from his rubbish bins only to turn up on the backs of other young men around town. They were obviously not quite as well fitting as when Alan wore them but they looked good enough to gain some attention of their own. Those who knew something about fashion recognised the source. They went to Alan to tell him about it and ask him to make clothes for them and finally he agreed.

He began to build quite a following for his unique tailoring style that took standard detailing and made it into something unexpected and new. There was quite a demand. He won prizes and appeared in magazine articles. Models competed to wear his styles in fashion spreads.

But then of course the knockoffs were thriving too. Alan could never hope to satisfy the hunger for his clothes by himself and it was unthinkable to hire assistants just to keep up with the orders. So the waiting list grew and sometimes people just couldn’t wait any longer. Gradually, a whole industry grew up with no other purpose, it seemed, than to watch what Alan made and then replicate it more cheaply. He didn’t take any of them seriously - they didn’t have the patience or the imagination to copy more than the surface details. But it was tiring, all the same. The feeling of being on a treadmill was stronger every day until he knew he had to do something before his desire to create vanished for good.

Then he announced to all his clients that from now on he would he putting all his resources into something new. He called it... the potatosack.

It didn’t catch on right away. It was rough and scratchy, provided no pockets for credit cards or cellphones, came in only one colour and one size and was no good in the rain. It certainly didn’t keep the cold out, either. But nobody wanted to be the one who didn’t ‘get it’, so eventually everyone who was anyone was wearing the potatosack.

The fashion magazines wrote about it endlessly. It spread inexorably to the cheaper stores who also sold cutdown versions for children. And just when it looked like there could hardly be anyone left in the entire city who didn’t own a potatosack, Alan was interviewed on TV. He was wearing one of his old suits. Why wasn’t he in a potatosack?

—Because it’s a joke, he said.

—You’re all wearing sacks made for potatoes, he said.

—Look at you. They’re impractical, ugly and itchy. They’re not clothes. They’re rough pieces of burlap. They’re only fit for carrying potatoes. Why would anyone with any sense voluntarily wear one of those ridiculous things when they could be warm and dry and comfortable in actual garments?

Imagine it. Every line to the station’s switchboards was instantly jammed and there were crazy scenes in the studio as the entire audience rose up as one and rushed the stage, knocking lights, cameras, cameramen aside in their frenzy. At some point order was restored and that was when they realised that Alan had vanished. A vengeful crowd searched for him while potato sacks burned in the streets, but his apartment was empty, his bank accounts closed and his office bare.

Six months later, halfway around the world in Technical Town, several people began to notice an unusual kind of software in use at a few terminals around downtown cafés... but that’s another story.

When Alan arrived in Mainstream City, he seemed to be the same as everyone else. He blended right in with all the residents with their hats and overcoats, though you might have noticed the fancier stitching and the rather higher than average quality material of his overcoat if you paid attention to such things.

He soon found himself a place to live and a job, made friends and went to church just like everybody else, but there was something about him that made him stand out. Eventually people figured out what it was. It was the way he dressed. Even though he wore the same things as everyone else, he wore them differently. It was all in the details. Hand finishing. Linings in unusual fabrics. Bias cutting. Seams that were stitched rather than fused or glued.

According to Alan there was nothing especially noteworthy about any of this. He came from a tradition of hard work and attention to detail, he said, and that was all there was to it.

However, while he had begun by branching out, by subtly altering the details of traditional tailoring, he began feel the restrictions of this approach. He decided to go further. He went off in entirely new directions with radical styles and some rather challenging choices of colour and fabric. People noticed. People talked. He became the focus of quite a lot of attention and speculation about what he might make next.

It was remarked upon that he never seemed to wear the same piece of clothing twice. He said it was true: there were so many styles in the world, why confine yourself to the same items over and over?

Not long after that, Alan saw that his discarded clothes earmarked for recycling were vanishing from his rubbish bins only to turn up on the backs of other young men around town. They were obviously not quite as well fitting as when Alan wore them but they looked good enough to gain some attention of their own. Those who knew something about fashion recognised the source. They went to Alan to tell him about it and ask him to make clothes for them and finally he agreed.

He began to build quite a following for his unique tailoring style that took standard detailing and made it into something unexpected and new. There was quite a demand. He won prizes and appeared in magazine articles. Models competed to wear his styles in fashion spreads.

But then of course the knockoffs were thriving too. Alan could never hope to satisfy the hunger for his clothes by himself and it was unthinkable to hire assistants just to keep up with the orders. So the waiting list grew and sometimes people just couldn’t wait any longer. Gradually, a whole industry grew up with no other purpose, it seemed, than to watch what Alan made and then replicate it more cheaply. He didn’t take any of them seriously - they didn’t have the patience or the imagination to copy more than the surface details. But it was tiring, all the same. The feeling of being on a treadmill was stronger every day until he knew he had to do something before his desire to create vanished for good.

Then he announced to all his clients that from now on he would he putting all his resources into something new. He called it... the potatosack.

It didn’t catch on right away. It was rough and scratchy, provided no pockets for credit cards or cellphones, came in only one colour and one size and was no good in the rain. It certainly didn’t keep the cold out, either. But nobody wanted to be the one who didn’t ‘get it’, so eventually everyone who was anyone was wearing the potatosack.

The fashion magazines wrote about it endlessly. It spread inexorably to the cheaper stores who also sold cutdown versions for children. And just when it looked like there could hardly be anyone left in the entire city who didn’t own a potatosack, Alan was interviewed on TV. He was wearing one of his old suits. Why wasn’t he in a potatosack?

—Because it’s a joke, he said.

—You’re all wearing sacks made for potatoes, he said.

—Look at you. They’re impractical, ugly and itchy. They’re not clothes. They’re rough pieces of burlap. They’re only fit for carrying potatoes. Why would anyone with any sense voluntarily wear one of those ridiculous things when they could be warm and dry and comfortable in actual garments?

Imagine it. Every line to the station’s switchboards was instantly jammed and there were crazy scenes in the studio as the entire audience rose up as one and rushed the stage, knocking lights, cameras, cameramen aside in their frenzy. At some point order was restored and that was when they realised that Alan had vanished. A vengeful crowd searched for him while potato sacks burned in the streets, but his apartment was empty, his bank accounts closed and his office bare.

Six months later, halfway around the world in Technical Town, several people began to notice an unusual kind of software in use at a few terminals around downtown cafés... but that’s another story.

The wonderful wardrobe of Alan Moore

written and illustrated by Woodrow Phoenix