|

| Iain Sinclair and Alan Moore, 2017 |

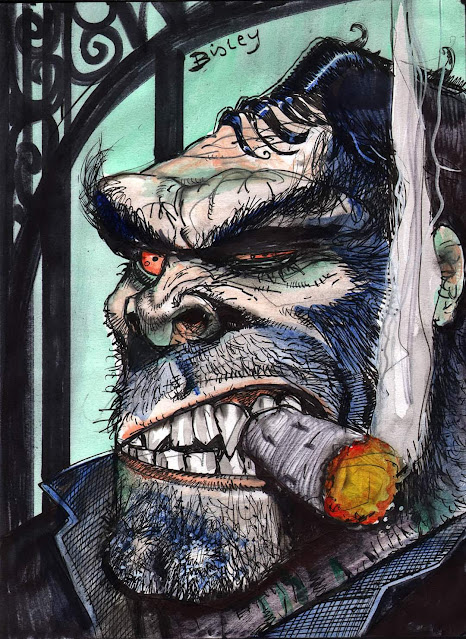

From the sold-out Alan Moore: Portrait of an Extraordinary Gentleman

book, below you can read the

contribution written by acclaimed Welsh writer and film-maker IAIN SINCLAIR to celebrate Alan Moore's 50th birthday in 2003.

Moore named Sinclair as one of his favourites writers (here) in several occasions.

Regime change in Whitechapel

Back in the dog days of the last century, before the restaurants in Brick Lane featured celebrity snaps of Prince Charles and a few dejected English cricketers on the piss and somebody in suit and tie who used to read the news (Falklands, Gulf War), a bunch of cultural subversives were gathered to enact, in their own ways, the last rites. The skeletal book-burner John Latham with his mad eyes and posthumous (slow, deadly) voice. Derek Raymond, jaunty, spry, fruity, smart, remembering what it had been like to be Robin Cook - and writing a cod-Bond novel that went so far off the rails that it froze time, a period in the Sixties, and entered all the dictionaries of slang. Poet and performance artist Brian Catling, shaven-headed, cigar-chomping, berobed, returning to scenes of vision and poverty, labours in the ullage cellar of Truman’s Brewery. Alexander Baron, solid but tentative, white raincoat like the negative of a lost life; post-war wanderings through a blasted landscape. And fellow Jewish memory-man, Emanuel Litvinoff, who once discussed alchemical epics with Elias Canetti. A few villains were also present: Tony Lambrianou, chauffeur to the rug-wrapped corpse of Jack the Hat, and the now vanished biblio-maniac Driffield. Then there was Alan Moore.

The excuse was a film for Channel 4, The Cardinal and the Corpse - which suffered from too many cardinals and not enough corpses (the dead wouldn’t lie down). Of all the faces who had to hang around, in Cheshire Street market, in the house with the peeling pink door in Princelet Street (now a regular feature in Dickens heritage romps), in the infamous Carpenters Arms (with its lost apostrophe), only one registered with the citizens, ordinary dishonest folk going about their business. ‘Are you,’ they challenged, not daring to believe it, ‘Alan Moore?’

Alan doesn’t quite believe it himself: that he is on set, grounded in the future of a definitively erased past, space-time anomalies he will activate in his serial composition, From Hell. This grimoire, with its fearsome apparatus of actual and fantastic scholarship, is the ultimate book on the Whitechapel Murders. The endstop. Many, many others, hacks, snoops, chancers, will follow - but they won’t register. Game over. Patricia Cornwell, the latest, richest, and most absurd, brings the weight (humourless, pan-global paranoia) of the CIA, forensic SWAT teams, art dealers, foot-in-the-door men to bear on a series of terrible Victorian crimes. She is the wrong book, straddled across the razor-wire of the genre fence. It’s like Miss Marple hitting Los Angeles to solve a slasher crime, the slaying of James Ellroy’s mother. Wrong game, wrong century.

Not content with world domination, America wants to invade the only thing we have left: the past. They devoured From Hell. They liked it and they bought the company. And made it into a ‘ghetto story.’ With punch, panache, zizz: the stuff they do so well. And with a brutal disregard for history, so that the pain (which burns through those stones still) of the butchering of Marie Jeanette Kelly is demeaned - by a narrative twist, wrong girl, and a happy John Ford ending in a whitewashed cottage in the west of Ireland.

Alan Moore knows that these sentiments can be floated as recalled potentialities, a single flash-frame in a dying consciousness, before the darkness sets in. One bead of bright light before an eternity of stygian black.

Loping down Princelet Street, with a kind of nautical roll, non-metropolitan - backlit Durer hair - Alan stands out; not belonging to these alleys and rat runs, he is visible in ways the other writers are not. The space between what he writes and what he is dissolves. He acts. The rest of them are what they do, talk, words - or quiet moments, caught at a window, of wounded reverie. There is a thing that won’t leave them alone, a vulture on the shoulder. ‘The general contract,’ Derek Raymond called it. Mortality.

Mortality imprints these streets like a miasma. Alan Moore, playing at the ‘discovery’ of a magical primer, plays at being trapped forever in this house, this place. And so it is. The Vessels of Wrath sail through the sky, clouds pierced by the steeple of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church. The extraordinary, hallucinogenic structure that has haunted artists and writers (from Leon Kossoff to Peter Ackroyd) catches Alan’s eye: a stone needle in a pane of dirty glass. The church, with its balanced weight and mass, marries disparate elements: Greek, Roman, Gothic. As Moore will balance the unwieldy mass of dark history, lies, forgeries, echoes of other writers, Blakean epiphany, Crowley ritual.

There are no accidents here. Moore, on the steps of the church, is passing through, gathering what he needs. The rough walkers, the vagrants, the invisibles who challenge him, are there for the duration; no parole. Shifting facades, fresh scams; nothing changes.

Iain Sinclair